Lloyd Webber

Aspects of Love

Phantom of the Opera

Starlight Express

Cats

Les Miserables

Miss Saigon

Metropolis

The Baker's Wife

Time

Stars of the Stage

An evening of encores

Mark Steyn on Andrew Lloyd Webber's latest addition to the West End, Aspects of Love

"Love - Love Changes Everything": like many clichés this one contains a good measure of truth and it serves as an efficient opener for a musical based on David Garnett's ménage à six. It's also less simple-minded that it seems: does love really change everything or, as the characters repeat the same mistakes across 17 years, is the sentiment merely self-deceiving?

The trouble is that everything changes except "Love Changes Everything", so that, as the evening goes on, Aspects of Love increasingly resembles one of those snow-scene knick-knacks with a built-in music box: every few minutes, it's shaken furiously and the scenery rearranges itself, but, after the dust settles, the same tune re-emerges. To take a few random renderings, we first meet Alex reminiscing at a French railway station in 1964:

"Love - love changes ev'ry thing.

Days are longer,

Words mean more".

Then we're back to 1947, and Alex resents his uncle's intrusion on his and Rose's idyll:

"Why? - why must he spy on us?

It was perfect

Till he came".

Two years later, Alex, on National Service, receives a letter from Rose:

"News - takes time to reach us here.

So you're married?

Well ... that's nice".

Another 15 years pass, and Alex's cousin Jenny starts singing the song back to him:

"What - what are you frightened of?", etc.

Now, there is a sort of logic behind this. Like Showboat, Aspects sprawls across the years and needs its own "Ol' Man River" to bind the three generations together. But, even if this were the most versatile tune ever written, it would still, eventually, become very dull. You can have reprises or you can have new songs, but I would respectfully suggest that what you cannot do is keep reprising the tunes with new words.

Uncle George, for example, has a philosophical line, "Life goes

on, love goes free", which could well be said to define the show.

At one point, in the depths of Alex's despair, the 14-piece orchestra

- with a lovely bitter-sweet café

sound - taunts him with the phrase, and the young man shouts, "You're

wrong, George!" Having established the line early on, Lloyd Webber

has deployed it very effectively: it's a moment of drama in music. But

by the time the phrase has been reprised as "Tell her that, then

you're free" and a dozen other lines sung by various cast members,

it's been so devalued as to be almost worthless.

It is unfair to his lyricists, as endless sets of words fitted to increasingly familiar patterns tend, inevitably, towards doggerel: in this respect, despite the occasional infelicity, Don Black and Charles Hart have done a marvellous job in unenviable circumstances. But the composer is also selling himself short, since, with each lyrical variation, the melody is further diluted: would the young Lloyd Webber have been as impressed by "Some Enchanted Evening" if it had popped up 10 minutes later as "Would You Like A Biscuit?"?

Tell Me on a Sunday, although through-written, told its story in songs, which played to Don Black's flair for titles and ideas and showed that Lloyd Webber could be as fertile a melodist as the best of them. Here, the score is so fractured that the most muscular melodies end up as libretto fodder and create the impression, particularly in the musically undernourished first act, that, for all the dozens of scenery shifts and relentless passage of time, the show is actually standing still. Perhaps Lloyd Webber should busy himself less with orchestration (although the sound is often quite beautiful) and more with composition. Much of the score sounds like linking passages from which one keeps expecting songs to break loose. But not until the far better second act do any really take off.

Throughout the evening, three different shows are jostling for position: Maria Björnson's manically restless sets and Gillian Lynne's circus divertissement are sops for those who are expecting traditional Lloyd Webber lavishness; the score and libretto layout trot along faithfully - too faithfully - after the structure of the novella; and it's left to Trevor Nunn's fine acting ensemble to come closest to distilling the easygoing sexuality of Garnett's characters. The eeriest moments rely on staging rather than score: Alex (Michael Ball), fighting to restrain himself, as he removes his jacket and shoes and climbs into bed with his 15-year-old cousin; the explicitly passionate embrace between Rose (Ann Crumb) and her husband's mistress Giulietta, played with careless sensuality by Kathleen Rowe McAllen.

Very little of this Continental contempt for convention is caught in the score. Lloyd Webber's musical passion is ardent and direct, swell for Phantom, but less suited to the many aspects of Garnett's characters - playful, sly, naive, malicious, reluctant. I refuse to believe that Giulietta would ever say: "He saw me through my DARKEST MO-MENTS!", but I sympathise with Black and Hart. Lloyd Webber's music is so self-regardingly formal that colloquial speech - "A glass of house white for me" - sits terribly uneasily, and the lyrics are permanently fighting against the dread pull of operetta certainties. That's fine in its place, but this series of rather more exotic relationships cannot be conveyed solely through uplifting ballads, all ending with a full-throated climb to the top of the register.

That said, Aspects is a zillion times better than Metropolis or Legs and Diamond and much perkier second act does offer two top notch songs, "Other Pleasures" and "The First Man You Remember", both of which go to Kevin Colson, who plays George splendidly as a shrewd old charmer. Here, for the first time in nearly a decade, Lloyd Webber offers us people we can care about in emotionally gripping situations. For that and his renunciation of spectacle, we must be grateful.

As for the merits of through-sung chamber opera, I'm still open to persuasion, but on the evidence of this score Lloyd Webber's power as a producer is not yet matched by his inventiveness as a composer. Those few people who have any influence over him should urge him to rethink drastically Act One, if not for London, then for Broadway. At the moment, 15 minutes in, you've heard all Act One's best shots and, as that realisation dawns, many theatregoers could feel short-changed. Andrew Lloyd Webber may be critic-proof, but is he audience-proof?

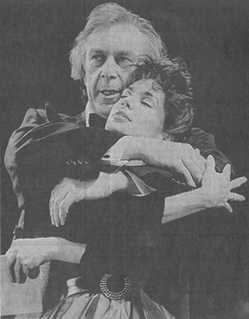

Kevin Colson as George Dillingham and

Kathleen Rowe McAllen as Giulietta (Geraint Lewis)

Mark Steyn, The Independent, 19 April 1989